Boudicca is perhaps best known for her heroic and successful revolt against the oppressive Roman Empire, known as the Iceni Revolt, which took place in 60/61 AD and forever changed the course of British history.

Boudicca was a wise and brave leader during the rebellion. She united the tribes of Britain to drive out the foreign oppressors and restore freedom and independence to the British people. In her campaign against the Romans, Boudicca employed guerilla tactics and captured several major Roman cities. She was eventually cornered and defeated in a bloody battle at the Battle of Watling Street in what is now Kent, England.

Boudicca’s legacy lives on to this day. She is remembered as an inspirational leader who stood up to tyranny and fought with courage and tenacity in the face of unimaginable odds. Her story is an essential reminder of the power of collective action and the strength that can be found in people willing to fight for what they believe in.

She has become a symbol of strength, courage, and resistance for the British people, who continue to celebrate her legacy in various festivals and monuments.

In 2002, a bronze statue of her was erected at the National Assembly for Wales in Cardiff, and every year, the Welsh celebrate her life and legacy with a festival in her name.

The Background to the Iceni Revolt.

“(she was a) … dreaded sight, terrible with brandished weapon, her form augmented by a tall stem bearing a corselet and a flowing veil”. - Tacitus

Boudicca was one of many Celtic leaders of Britain during the Roman “Invasion”.

The Celts were a powerful and influential group that inhabited Britain. They had a diverse set of beliefs and were renowned for their fierce warriors. They were divided into many distinct tribes with unique customs and traditions.

They were known for their strong sense of community and loyalty and often worked together to protect their lands and defend their rights.

They had their own form of government and kept their own legal systems, with each tribe ruling according to its laws. Their culture was vibrant, with music, art, and literature flourishing.

This, of course, was not the way Roman historians presented these tribes of people.

Boudica was the consort of Prasutagus, king of the Iceni, a tribe who inhabited what is now the English county of Norfolk and parts of the neighbouring counties of Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and Lincolnshire.

They had revolted against the Romans in AD47 when the Roman governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula, planned to disarm all the peoples of Britain under Roman control. The Romans allowed theIceni to retain its independence once the uprising was suppressed

On his death in AD 60/61, Prasutagus made his two daughters and the Roman Emperor Nero his heirs.

The Romans ignored the will, and the kingdom was absorbed into the province of Britannia. Catus Decianus, the procurator of Britain, was sent to secure the Iceni kingdom for Rome.

The historian Tacitus described the Romans' next actions, detailing the pillaging of the countryside, the ransacking of the king's household, and the brutal treatment of Boudica and her daughters.

According to Tacitus, Boudica was flogged, and her daughters were raped.

Another Roman writer,

These abuses are not mentioned in Cassius Dio's account, which instead cites three different causes for the rebellion: Seneca's recalling of loans given to the Britons, Decianus Catus's confiscation of money formerly loaned to the Britons by Emperor Claudius and Boudicca's own entreaties.

The Iceni claimed that the loans to have been repaid by gift exchange.

The Boudiccan Revolt.

The treatment of the Iceni led to an armed uprising by native Celtic Britons against the Roman Empire. It occurred circa AD 60–61, led by Boudicca, now recognised as the Queen of the Icenit.

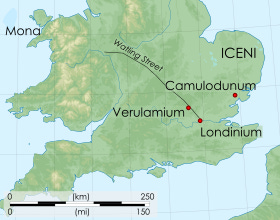

The revolt's timing was not good for the Roman Empire. While the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was leading a campaign against the island of Mona (modern Anglesey) off the northwest coast of Wales, a refuge for British rebels and a stronghold of the druids, the Iceni, with their neighbours, the Trinovantes, amongst others, began their revolt.

The rebels' first target was the former capital of the Trinovantes, Camulodunum (Colchester), which had been made into a colony for Roman military veterans.

These veterans had been accused of mistreating the locals.

A huge temple to the former emperor Claudius had also been erected in the city at great expense to the local population, causing much resentment.

The future governor, Quintus Petillius Cerialis, then commanding the Legio IX Hispana, attempted to relieve the city but suffered an overwhelming defeat. The infantry with him were all killed, and only the commander and some of his cavalry escaped.

The Roman inhabitants sought reinforcements from Catus Decianus, but he sent only two hundred auxiliary troops. Boudica's army attacked the poorly defended city and destroyed it, besieging the last defenders in the temple for two days before it fell.

Archaeologists have shown that the city was methodically demolished.

When news of the rebellion reached Suetonius, he hurried through hostile territory to Londinium, a relatively new settlement founded after the conquest of AD 43, which had grown to be a thriving commercial centre with a population of traders and probably Roman officials.

Suetonius considered fighting the rebellious tribes there, but with his insufficient numbers of troops and chastened by Petillius's defeat, he decided to sacrifice the city to save the province and withdrew to regroup his forces.

The wealthy citizens and traders of Londinium had fled after the news of Catus Decianus defecting to Gaul. Suetonius took with him as refugees those citizens who wished to escape, and the rest of the inhabitants were left to their fate.

The rebels burned Londinium, torturing and killing everyone who had not evacuated with Suetonius.

Archaeology shows a thick red layer of burnt debris covering coins and pottery dating before AD 60 within the bounds of Roman Londinium.

Verulamium (modern St Albans) was also destroyed.

In the three settlements destroyed, between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed. Tacitus says that the Britons had no interest in taking or selling prisoners, only in slaughter by gibbet, fire, or cross.

The Final Battle

According to Tacitus, while the Britons continued their destruction, Suetonius regrouped his forces, rallying almost 10,000 men.

At an unidentified location, Suetonius took a stand in a narrow passage with a wood behind him that opened out into a broad plain.

His men were heavily outnumbered.

At this time, some exaggerated suggestions were made that the rebel forces numbered 230,000–300,000. Whatever the actual number, Suetonius’ men were considerably outnumbered.

The sides of the passage protected the Roman flanks from attack, and the forest impeded approach from the rear. This was a clever piece of strategic thinking since it prevented Boudicca from bringing her considerable forces to bear on the Roman position other than from the front, and the open plain would have made a surprise attack impossible.

Although the Britons were gathered in considerable force, the Iceni and other tribes had been disarmed some years before the rebellion, and it is thought they may have been poorly equipped.

Tacitus’ writing much later, imagined Boudicca’s rallying speech..

But now,it is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, and the outraged chastity of my daughters. Roman lust has gone so far that not our very persons, nor even age or virginity, are left unpolluted. But heaven is on the side of righteous vengeance; a legion which dared to fight has perished; the rest are hiding themselves in their camp or are thinking anxiously of flight. They will not sustain even the din and the shout of so many thousands, much less our charge and our blows. If you weigh well the strength of the armies and the causes of the war, you will see that in this battle, you must conquer or die. This is a woman's resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves.

The same historian imagines Suetonius’ rallying call…

Ignore the racket made by these savages. There are more women than men in their ranks. They are not soldiers — they are not even properly equipped. We have beaten them before and when they see our weapons and feel our spirit, they will crack. Stick together. Throw the javelins, then push forward: knock them down with your shields and finish them off with your swords. Forget about plunder. Just win and you will have everything

The battle did not go well for Boudicca and her forces.

The Roman forces were disciplined, well-equipped and positioned strategically.

After the battle, Tacitus says Boudica has poisoned herself. However, in another text written almost twenty years before Tacitus, there is no mention of suicide, and the end of the revolt is attributed to complacency.

Neither classical historian identified the battle site, although Tacitus mentions some of its features; its location is unknown.

Most modern historians favour potential location sites in the Midlands, possibly along the Roman road between Londinium and Viroconium (Wroxeter), which became Watling Street.

Archaeologist Graham Webster suggested a site near Manduessedum (Mancetter), near the modern town of Atherstone in Warwickshire.

Kevin K. Carroll suggests a site close to High Cross, Leicestershire, at the junction of Watling Street and the Fosse Way, which would have allowed the Legio II Augusta at Exeter to rendezvous with the rest of Suetonius's forces if they had come as ordered.

After the Romans suppressed Boudicca's rebellion, Britons mounted a few smaller insurrections in the coming years, but none gained the same widespread support or cost as many lives. The Romans would continue to hold Britain without any further trouble until they withdrew from the region in 410.

Boudicca's story was nearly forgotten until Tacitus's work, "Annals," was rediscovered in 1360. Her story became popular during the reign of another English queen, Queen Elizabeth I, who led an army against foreign invasion.

Today, Boudicca is considered a national heroine in Great Britain, and she is seen as a universal symbol of the human desire for freedom and justice

Statute of Boudicca and her daughters on Victoria Embankment London (1902)

Final Thoughts.

As with so much of our history there is always the risk of being overly romantic, especially when talking about folk heroes.

Boudicca’s story has themes of oppression, tyranny, sacrifice and martyrdom. Themes which still resonate.

We must also consider that Boudicca represents a woman’s rejection of male domination. While Celtic tribes and rulership seemed far less dismissive of women, Boudicca is a testament to their inspiring and powerful women.

Suppose the treatment of her and her daughters as described by Tacitus, is in any way close to the truth. Then, Boudicca’s torture and the defilement of her daughters is a brutal reminder of how men have and still can disempower women by act, deed or insinuation. The legend of Boudicca contains the enduring message that one day, the oppressed will rise!

"If you weigh well the strengths of our armies you will see that in this battle we must conquer or die. This is a woman's resolve. As for the men, they may live or be slaves." "I am not fighting for my kingdom and wealth now. I am fighting as an ordinary person for my lost freedom, my bruised body, and my outraged daughters."

Alan /|\